Posse Power |

|

|

The Face Volume 2, Number 30 March 1991 Page: 42 |

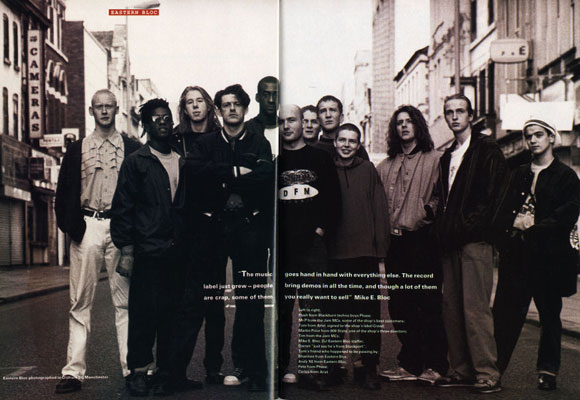

EASTERN BLOC is the Manchester record shop which launched 808 State on their own label, Creed. Upcoming releases include Ariel's "Sea Of Beats" (remixed by Justin Robertson, one of several DJs working at the shop); "LMF Mixes" by Blackburn techno boys Phase; "Rhythm Is A Mystery" by K-Klass; "Green Ray" by Sun Kings; and "French Connection" by DJ Laurent Garnier. The shop, still co-owned by 808 State's Martin Price and still specialising in quality dance music, is at 5-6 Central Buildings, Oldham St, Manchester Ml (mail order on 061-2364300)  Left to right: If the pop hero is no more, perhaps that's because the pop group is fading fast. The old group idea - a singer, bassist, guitarist, drummer and perhaps others who record an album, release some singles from it, and then go on tour to promote it - is being replaced by new, more flexible collectives. Partly, the reason is technology. When your drummer can be replaced by a machine - when almost any instrument, in fact, can be imitated by a computer - there's no need for a fixed line-up of musicians. Especially since it is no longer essential to play live. Dance music sells mainly through being played by DJs in the clubs, and the video has long since replaced the tour as a means of promoting pro-duct: it's cheaper, quicker, and can be seen all over the world at the same time. Even traditional groups are diversifying - when you make more money from your T-shirts than your records, the person who designs them is central to your crew. Likewise, bands may be aware that at least part of the attraction for their fans is not their live set but the DJ who plays before and after they hit the stage. Former indie rockers like The Shamen are less a group now than a mobile club - lighting and sound technicians, DJs and rappers are all as integral to their impressive live events as the musicians who make up the core of the group. And without the need to be constantly on tour, musicians are free to contribute to other projects. "Ex.el", the new LP by 808 State, features contributions from Bjork Gudmundsdottir of The Sugarcubes and Bernard Sumner from New Order, and no one finds this at all surprising. Nor does it seem strange that when Norman Cook left indie champs The Housemartins he went on to form Beats International, a loose collective that can include anyone from a former soap actress to a graffiti artist and which produced "Dub Be Good To Me", one of the best-selling singles of 1990. In British dance music, the roots of collective working lie in the sound system, essentially a mobile disco which evolved into something much more as everyone around it contributed what talents they had: hauling gear, mixing records, rapping or singing on the mic, building the huge speakers or painting them with trademark designs. But, inevitably, American hip hop - a music which developed when the reggae sound system moved from Jamaica to the Bronx - picked up on the posse ethic first. Working in loose collectives made sense, from Afrika Bambaataa's Zulu Nation right at the start to current 'families' like the Native Tongues (Queen Latifah, De La Soul, Jungle Brothers, Monie Love, A Tribe Called Quest); Mark 'the 45' King's Flavor Unit (Chill Rob G, Double J, Latee, Queen Latifah, Apache, Lakim Shabazz); the Juice Crew (Roxanne Shanté, Biz Markie, Marly Marl); KRS1's Boogie Down Productions; and the Muslim, politically-motivated, X-Clan. Few British rap crews are strong enough to work as permanent collectives but, in Japan, the Major Force posse follows its American model. In Britain, families like London's Soul II Soul or the singers and rappers grouped around Bristol producers Smith & Mighty grew directly out of sound systems. Soul II Soul were a sound first, then a club, then a record/clothes shop, and only after several years did they become recording artists, producers and remixers. "We work this way because it's all we've known," says Jazzie B. "It's the same principles as when we were a sound - we're a gang, a posse, we all know each other, what we can do, our temperaments and limitations. We've done things backwards, really - most people start the group first. But it all came very naturally; one thing just led to another." Newer converts to collective working find it more comfortable than the old ways. The Brain's Sean McClusky was once in Jo Boxers, who briefly tasted chart success in 1983. While working on his new band If?, he was offered the chance to open the Brain club in Wardour St, London in partnership with artist Mark Wigan: "I just couldn't say no. In fact, it turned out useful because it gave me a profile again and that rubbed off on the band. Through the Brain tours, we played places we wouldn't have got offered at the time. I feel much more secure than before. I've got other things on the go, a social scene. It gives us some roots, and a place to play - I'll always book us for a tenner, even if no one else will!" George O'Dowd, too, says he doesn't miss the kind of global fame he enjoyed with Culture Club, working profitably instead on small-scale dance records with old friends like E-Zee Possee's Jeremy Healy. "I'm happier now. There's none of the same ego problems. Collaboration is the key to good work. As soon as you label something, it starts to be a problem. Everyone starts jostling for position. With More Protein, if we want to work together we do - if not, we don't." In the current climate, the key to success is diversity, using collective skills to branch into as many areas as possible. Record shops do more than just sell records - they spawn labels, promote clubs, offer daytime jobs to DJs and generally act as a meeting place and clearing house for ideas and information. Likewise, a fashion emporium such as London's Duffer of St George can produce a club and a group; a club like The Brain, Dave Dorrell's Love or Gilles Peterson's Talking Loud can inspire a record label; or a fanzine like Boys Own can branch out into parties, then remixes and productions, and finally a label of its own. Few of these moves were planned. As Mike E. Bloc from Manchester's Eastern Bloc explains, other activities like their dance label, Creed, grew organically from the record shop: "The music goes hand in hand with everything else. You get in the new tunes and you want to hear them in a club straight away, so you start DJing or promoting clubs of your own. The record label just grew - people bring demos in all the time, though a lot of them are crap." Nor are the posses mutually exclusive. The Bristol bunch spawned Massive Attack - who are now managed by Neneh Cherry's West London posse - and Nellee Hooper, who has co-produced most of Soul II Soul's successful records and mixes as well as Sinéad O'Connor's "Nothing Compares 2 U". In New York, Queen Latifah works with both the Native Tongues and the Flavor Unit. There are disadvantages too. Record companies, admitting they are increasingly out of touch with the market, have tended either to license smaller labels run by specialists or to sign complete packages - acts that come complete with songs, images and producers, the kind of music produced, in fact, by collectives. But these collectives can be faceless - just who are Snap anyway? Since the groups have few permanent members, key people can drift away or move into more lucrative solo activities. For many, Caron Wheeler was Soul II Soul, and are Beats International likely to scale the same heights without Lindy Layton? Inevitably, central figures emerge to front the records - Jazzie B as the face of Soul II Soul, Norman Cook as the key to Beats International - and resentments amongst other posse members can surface as a result. Meanwhile, Smith & Mighty, who have resolutely refused most interviews and all photo sessions in a bid to remain anonymous producers, have found the chart success their music deserves elusive. Martin Price of 808 State insists that it isn't easy to shake off the shackles of the traditional pop group once you reach a certain level. Other Manchester dance acts like K-Klass - signed to Eastern Bloc's Creed label - are having to emulate their example and act like a traditional group in a bid to reach a wider audience. 808's DJ members The Spinmasters still do their Tuesday night mix show on local Manchester station Sunset, and play the city's Sound Garden club on free Saturdays, but they have also been pressured to perform live to promote their music even though, as Martin freely admits, "We couldn't go out there and play the music on our records live even if we wanted to." But, he explains: "If you're big enough, you have no choice. You can only go so far without being seen on stage, in America especially, and record companies still want that. People just don't understand you otherwise." He enjoys collaborating with other people - a natural next step for DJs used to working with established names through remixes only, "and it's more satisfying because it's more personal". "The North At Its Heights", the album they produced for MC Tunes, "set a precedent", he agrees. "Normally our record company ZTT wouldn't put up with it. It was only because we were very insistent and had a very good contract that we got our own way." Sheryl Garratt Thanks to Ekow Eshun |

|