Genius Plastic |

|

|

Q April 1991 Page: ?? |

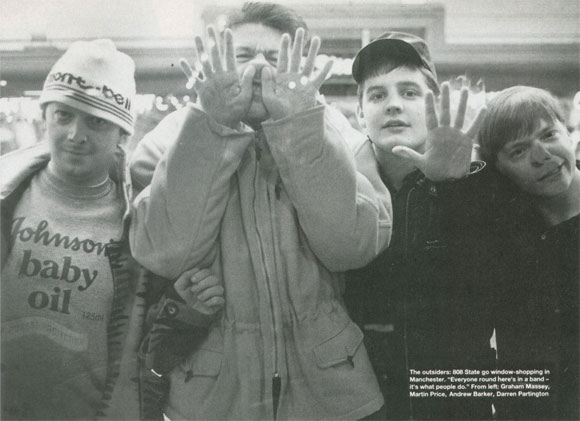

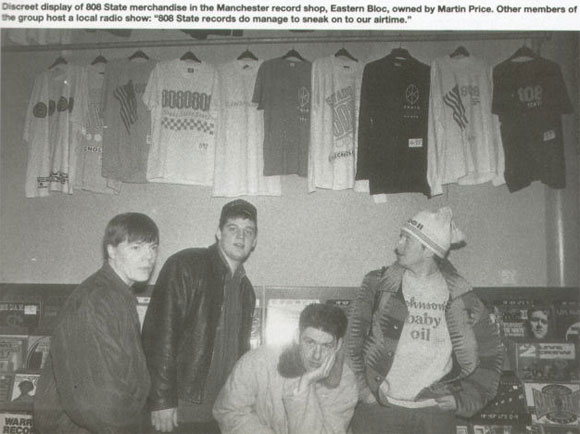

The roar of the greasepaint, the smell of the crowd ... 808 State don't give a stuff about it. Why be lumbered with fat drummers when you can make the records you want with a gadget you can play in a bedroom? "We break rules every other day," they warn Lloyd Bradley. Eastern Bloc Records in Manchester's rapidly becoming-fashionable Oldham Street is, at first glance, no different to any other specialist dance music emporium. Kilometres of rack space offer an up-to-the-minute catalogue of all things funky (sub-divided into your domestic and your imported floorfiller); a sound system of foundation-shifting potential pumps out a seamlessly-segued selection of trainer-friendly noises, and trade is plied with nods and gestures worthy of Sotheby's, since decibel-level rules out conversation. Customers clustered around the chest-high counter who wish to settle up an account deploy full-body sign language with a skill seldom seen since the days of Vision On. But what's unusual here is the T-shirt display - over 50 per cent of the designs involve 808 State. This is more than a celebration of the local lads' chart singles, Pacific State and Cubik Olympic, or a marketing wheeze to cash in on their new album, Ex El. In the saga of 808 State, Eastern Bloc is a corner-stone. Owned by group member Martin Price, it's where the quartet - Price, Graham Massey, Darren Partington and Andrew Barker - first met. In many senses, this is home to the group; it's where they're surrounded by, can listen to, gaze upon, earnestly discuss the merits of or just feel the vibe from a seemingly limitless supply of the love of their lives. Records ... 808 State are unrepentant vinyl junkies, or as Price's flat-vowelled humour has it, "obsessed with circular pieces of black plastic". They'll pronounce a good record to be "genius plastic" with the same reverence that you hear "good arrers" being bestowed on the three-in-a-bed darter. And this is no kneejerk reaction against the now-fashionable notion of playing "real" music at "real" gigs, this four-some have long-standing habits. Alit the band own the sort of collections that'll see the burliest removal man on the osteopath's couch, and prior to 808 State, each turned his hobby into profit: Price sold records; Barker and Partington were active club DJs; and Massey was a trained studio engineer. Forming the group, he says, was the logical extension of their obsessions. "Right from the word go we wanted to make records," he enthuses. "We were never interested in 'being in a band', and performing on stage and all that goes with it - being stars and wrecking hotel rooms and the like. It was alit about getting the product out." "When you go into the music business," Price' expands, "and everyone round here's in a band - it's what people do - you make up your mind what you want to do: be an act and perform; or are you going to make records? We wanted to make records, and it's what we've continued to do." This, they claim, is the sensible approach for any forward-looking group of the 1990s. They feel the ever-expanding range of increasingly affordable technology is more geared towards studio work than stage performance, and that popular music's appeal is fast moving away from personalities. Also, they add, being studio-bound is sound business sense. As Price explains, anybody with £600 to spare can record their own single and get 500 white label copies pressed up. Unloading this initial run to local shops is "dead simple with a record nobody's ever heard before", leaving the act with at least £200 profit. If the record proves popular with clubs, shops and local/pirate radio, then a higher wholesale price for the second (greater quantity) pressing can be negotiated. A nice little earner of up to a couple of grand, easily enough to make another one. Although it might work best in specialist markets such as dance or reggae - avid fans and radio/club DJs to whom uniqueness is paramount - it can have wide-reaching results. "When you suss it out," Massey enlarges, "you realise that in the time it takes the average band to negotiate a deal with a record company, they could have put half a dozen singles out. We'd done two albums before we signed, and had a hit. It can give you a bit of clout." 808 State started life three years ago as Price's Hit Squad - performing at clubs, from the DJ booth, with Partington and Barker's turntable antics supplemented by synth work and mixing by Price and Massey. Gerald Simpson (A Guy Called Gerald) was part of this crew, but dropped out amid much acrimony - he later recorded a B-side called Specific Hate - and the four renamed themselves after a Roland drum machine. They made two albums for themselves (Newbuild and Quadrastate), before coming to the attention of ZTT Records (now part of WEA) via an unlikely leg-up from a DJ - Radio One's 'Wooh" Gary Davies: "He played Pacific State, which was first on Quadrastate, everyday on his Non-Stop Half-Hour and other Radio One DJs were getting mad because they couldn't get a copy to play." According to Partington, at least 100 examples of 808 State's cottage industry approach will be on offer in local record shops at any given time. "Not very many of them are particularly original," he says, adding that few of them have the unlimited access to new and influential material that 808 State's day jobs allow them. As a record shop owner, Price not only knows what sells, but must wield influence over his staff's turntable selections. Partington and Barker DJ in the area's hippest niteries and front a popular show on a community radio station (808 State records do manage to sneak on to our airtime"). And, as a trained studio engineer, Massey knows how to achieve the desired effects. But could these advanced qualifications in all things "dance" result in 808 State simply making records to a guaranteed-successful formula?  "It is a formula," Massey admits. "It's just not the traditional formula of Johnny on guitar and Ringo on the drums ... " "That formula is going on much more than this one," agrees Price. "It's just not that successful any more. It takes four hours to get fat Dave and drum kit into the lift and up into the studio, six hours for him to set up and you're paying for that time. We've all been through that and it's not relevant today. Now you can take the technology home, muck about with it in your own time and bring your contributions to the studio ready to go ... " "It's all a matter of knowing your music," concludes Partington. "We do, because of what we did before. If it was all put together cynically, we wouldn't spend so much time shouting at each other." In fact, it is the breadth of their contributions that seems to give 808 State the edge. Massey (a competent musician on a range of instruments) and Price's influences go back to their early '70s adolescences to include most thing electronic or experimental jazz/funk, Kraftwerk, Stevie Wonder, Depeche Mode, Faust - plus the less lab-like sounds of Philly and Northern Soul. This comprehensive grounding has given them a feel for melody and an appetite for experimentation. Indeed, they'll supplement their vast catalogue of potential music samples with anything that sounds interesting: domestic noises, computer-generated feedback sounds, TV advert soundtracks and cheesy film music are all brought into play. "We break rules every other day," reckons Price. "I'm the Brian Eno of Bolton, he's the Robert Fripp of Manchester."  Perhaps the secret of 808 State's success lies in the marriage of this Northern noodling with more familiar hip hop beats. Partington and Barker, both in their early twenties, have been hip hop DJ-ing for eight years. Their turntable-rotating careers began at a Salvation Army disco where they could get access to the equipment for quick-mix practice sessions and "run a crisps and Kit-Kat scam" to subsidise record purchase. They ended up DJ-ing all the area's Sally Army hops before dubbing themselves The Spinmasters to become Manchester's top crew. Between them they anchor Price and Massey's often esoteric soundscapes to solid dancefloor rhythms. As an instrumental group, 808 State's success has been little short of remarkable. The suggestion that they add a vocalist to the ensemble meets with a frosty reception from Price: "None of them want to work with us," he snorts. "We've often got to a point when we could bring a house-type gospel-ish singer in," says Massey, "but when they come to the studio we find out it just doesn't work, and although they're very polite, they know things aren't going right. Now we've got to the point where they approach us. Bjork and Bernard Sumner (singers with The Sugarcubes and New Order, who both feature on the Ex El album) came to us, and worked with what we'd got. If they hadn't done that, there'd be no vocals on the album. After all, it's only the mainstream needs singing, and we'll survive outside of that." The American record company, however, sees it slightly differently. While their UK label cheerily accepts what they do, America feels that without a stage show built round a frontperson, the band lack a focal point and selling focus. Again, 808 State aren't too worried. While they don't see themselves as shadowy, backroom figures, debates on presentation don't occupy too much time - their ideas for a forthcoming show at the G-MEX Centre involve an approach to performing in the round that most US promoters would have difficulty coming to terms with: "We'd like all the seats taken out, and we'd be in the sound booth in the middle, with the kids all around us on the same level, going mad." As for the US, they know they've made inroads into college radio, and feel that if progress on their terms takes a long time then "So what?". European and domestic sales should pay for the studio they want to build. "We're having a really good time making records," shrugs Price. "We get paid for it and - we think - it's really artistic. But," he adds, the businessman in him thinking aloud, "if the Americans want to put $5 million on the table . . . bring on the lurex!" |

|