| State's Evidence | |

|

Future Music Issue 7 May 1993 Page: 19 |

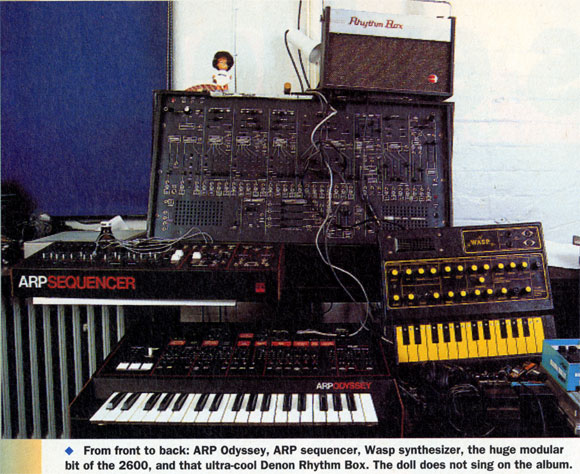

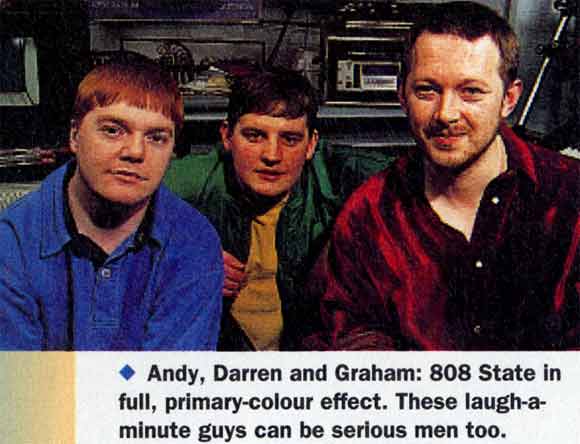

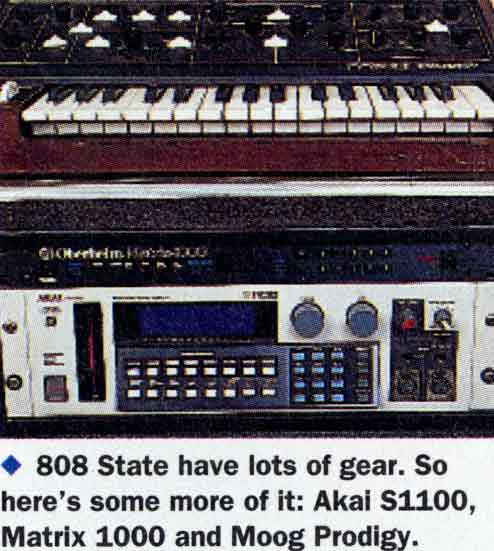

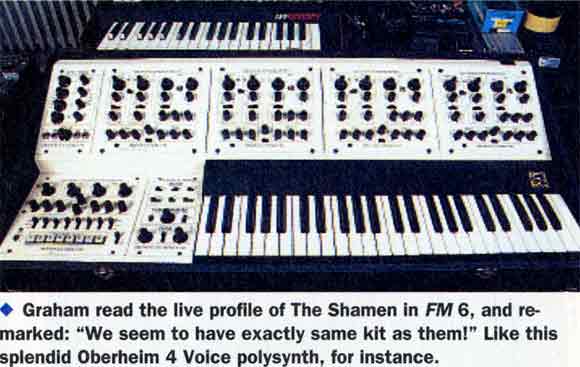

What's this? 808 State in grunge-techno-crossover shock? Or is it just a rather cool and intriguing photo gimmick? Dave Robinson heads up to Manchester to find out. Some things are the same for musicians everywhere. If you're serious about making a living out of music, chances are you'll try to find a bunch of soul-mates to help you. Mates with the enthusiasm, the commitment and, most importantly, the right kit. This was certainly the case back in the late '80s, at the conception of 808 State. "Half the time it was just about getting enough MIDI leads together," laughs Graham Massey, guiding hand and techno-spokesman for the band. "You became a group because you couldn't afford the gear on your own!'' 808 State have spent most of their five-year existence as a quartet (though Gerald Simpson, AKA A Guy Called Gerald and owner of the original Roland TR-808 drum machine, made it five at the outset). Fourth member and owner of Manchester's Eastern Bloc records, Martin Price, left the band over a year ago - an event that Graham refers to as the "divorce" - to follow other paths with another band, Switzerland. The three remaining members - Massey, Andy Barker and Darren Partington - produced the fifth 808 album in the New Year. The title, Gorgeous, is a superbly apt description . of the album's music. Whereas Ex:El, the previous album, had a certain hardness and harshness about it, Gorgeous exudes a warmth that is positively glowing. "There's a definite feeling of 'up' on Gorgeous", agrees Graham. The tracks are far more compact than previously, too. Ideas come and go quite quickly, and it's usually all over after about four minutes. In comparison, the first 808 album, Newbuild, had one idea lasting a whole side. "We had lots of ideas to get in," Graham explains. "We just didn't feel the tracks should be longer. [Digidesign's] Sound Tools was used to edit down sections that went on too long." The result, is a variety of flavours, with a diversity of feels: an ambient-style core; harder elements of dance; and an obligatory disco skit called Sexy Dancer. "We like the camp style of New York disco, you can trace it through every album that we've done."  State-registered verse As with Ex:El, there is a smattering of songs too. And as before, 808 State only employ vocalists with interesting or distinctive voices: on Ex:El it was Bjork from The Sugarcubes and Barney from New Order; now it's lead Bunnyman Ian McCulloch and This Mortal Coil's Caroline Seaman. "Songs aren't something we think we excel at," he admits. "We've only dabbled with songwriting a bit. A lot of the time it's been a case of 'Well, we've got some time left, let's do a song!', so we should really spend more time on them. "Doing a song is very satisfying, 'cos it's a different approach to the instrumental stuff. The points of interest are very different. "I think songwriting is something we'll grow into, rather than fall into. We love doing the instrumental stuff, but we can't expect everybody to like a whole album of insane micro-twiddling!" Knobs stay further untwiddled with the use of natural instruments alongside the electronics. Guitar, sax, and clarinet are all to be found on Gorgeous; Graham taught himself to play wind instruments by, as he puts it, "dicking about" over the years. "There's a real movement towards bringing the extra dynamics of natural instruments in. But using real instruments has always been part of the 808 sound." True, that was a real sax on Pacific State, for instance. So are these extras there to increase the live interest? Is it because so-called natural synth sounds are just not realistic enough? "It's because we get bored really," Graham says flatly. But it's also about being innovative. "If you use real sounds," Andy explains, "especially in dance music, it's a change, it gives a track a different edge."  State of mind So how do 808 State get their tracks together? The answer is deceptively simple, as Andy begins: "We'll sit down and decide what kind of track we're going to do." "Yeah, it's usually like, 'Ave you heard that track what goes like that?" interrupts Graham in his very broadest Mancunian accent. "'Well, we'll keep that feel but change it round." "To be quite honest," he admits, "we're always copying other people's stuff: recapturing a feel that we've heard on the dance floor, but then turning into something new, giving it the 808 edge. Like, Reaper Repo was inspired by a certain track, but it sounds completely different to that original The three have all got their own set-ups at home, so they can work on ideas before bringing them to the studio for looping and further programming. "It's more about organising choices rather than having a clear vision of how something will sound. We never structure things with [Steinberg's] Cubase too much; in that way we have a lot of options." explains Graham. To this end, parallel tracks will be recorded with, say, not one but several bass lines so that they can experiment by dropping them in and out. All the ideas are recorded to tape, which can cause confusion for remixers: "Our multi-tracks are often a nightmare for others because they don't make any sense whatsoever," Graham continues. "Accidents are kept on the tape too; I think it's really important that all the little tweaking bits are captured. I'm really into the idea of recording accidents and any quirks that crop up. "Then we'll all sit down for a mix, and that's when the shouting starts!" he laughs. " We always end up with four or five mixes of things because we have different opinions on the way a track should go. The mix is almost like playing an instrument; you get more feel into a track if you treat it like that. "Very often there are four or five versions of one tune on a single: different directions for different jobs. Darren and Andy, being DJs, have a very solid view of what's useful in a club. I tend to be a bit wayward from that, which is sometimes good and sometimes bad."  State opening Plan 9, the opening track of Gorgeous, contains those major seventh chords so distinctive of Pacific State, the track that really put them on the map and in the charts in '89. Was this an intentional inclusion? "We're aware of trying not to get stuck into set patterns and routines," says Graham. "One of the worst things in the world is when you sit down in front of a keyboard and you think 'Oh no, it's those chords coming out of my fingers again!' and 'If I put Polo mints between my fingers maybe I'll come up with something else!' We're always trying to break that down in everything we do, but occasionally the traits still come through." One method of exploring new possibilities is to experiment with analogue sequencers. "We recently got an old ARP sequencer, which is like having a [TB-]303 for the [ARP] 2600." Graham enthuses. "Exclusively Analogue are building us an interface for it that goes the other way round to normal: you can use a CV sequencer with a MIDI keyboard. I love the randomness of a CV sequencer; you can sit at it for ten minutes and come up with stuff you'd never come up with if you sat at a computer screen. We're into different ways of sequencing like that. For instance, we've used the Oberheim Cyclone arpeggiator quite a lot." On the day it arrived, it was hooked up to as many synths as possible. The sparkling results can be heard on Nimbus. "We use the internal sequencer and arpeggiator on the Memory Moog, and the arpeggiator on the Jupiter 8 for coming up with lines too. They're run off the [TR-]909 click trigger." Surprisingly, the 909, with it's definitive techno and house sounds, takes second place for percussion to a Roland JD-800. "We get a lot of mileage out of the JD-800. We use it more like a drum synthesizer rather than just a sample source," says Graham. "Like, you can take a CR-78 snare which is very 'biscuit-tinny' and add a little bit of a metal sample to it, but only so that you can only 'sense' it, rather than hear it. It makes everything a lot harder. "Also, you can take something like an 808 bass drum, and put a pitch envelope over it, so it goes 'whoop! whoop!' [imagine a noise like a sci-fi siren]. When you hear that coming out of a PA you think 'Yeah, we're doing it!'. "We use the JD for.-pads and things like that; but we do quite a lot of work on the sounds. Despite the fact that it looks like a really 'deep' synth, which it is, it's got an instantly recognisable sound. I can always spot a lot of modern synths on adverts on TV. Therefore, you mustn't over-use something like the JD; you have to use several different synths to get that contrast in sound, and you have to work on sounds to give them your own identity."  The Roland R8, once used heavily for drums, has now lost favour with the guys. "We've just grown out of using it," shrugs Graham. "I just like synthesizing drum sounds instead. We've started to use the 2600 for synthesized drums too after we read about Vince Clarke making his own! And we use the old Pearl Syncussion unit too: we like sampling and layering sounds from that. You have to get a uniqueness to drums, 'cos that's something that always sounds the same on dance records." 808 State are so often photographed with their ARP 2600, it's as though they have some overwhelming affection towards the dinosaur. This isn't far from the truth, as Graham waxes nostalgically, "There's something romantic about the look of the 2600. And if you listen to old Stevie Wonder albums you can recognise the unique sound. It's absolutely nothing like the Moog. If you've listened to a lot of music over the years with the character of the 2600 in it, when you come to use the synth, you feel like you're in touch with it. You know your starting point. It's a machine with roots. "Sometimes we find the sounds of the 2600 don't have enough definition. So if you sample it with the filters open a little more, you get drift; that phase shifting that can be frozen with the sampler. In that way you get the analogue warmth, the character of the 2600, but you get the definition too." The Moogs, especially the Mini, are favourites. "The Moog's got the most bollocks to it. There's something about the filters that really give the bass weight in a track. It's rare we move away from it for bass. "Sometimes we use the Juno ]cos it's got a lot of sub•to it. And often we make combination sounds, like a Moog mixed with something digital like the MicroWave. The bass is very important: it's the foundation of a track, and it's something we pay a lot of attention to." A digital edge is essential to the band, in their sound and in their philosophy. Graham elucidates: "There's a fine line between the pastiche thing and using the roots of music in a modern, creative way. It's the fine line Lenny Kravitz is always walking, you know? Using original microphones and stuff. He's not quite modern enough, if you know what I mean. "808 do have a reverence to the past and to the history of music and recording, but we also realise that we're at a revolutionary point with the technology now; therefore our sound should be to do with the new technology as well as the old. "People are always harping on about analogue gear. Well, we have a deep respect for that, but an equal respect for the future. All the way through 808 State it's been a question of balance. It's like...", he pauses, then laughs, "it's like cooking; you've got to get the ingredients right to make a good dinner."  Taking the state Getting samples cleared for Gorgeous, including those from songs by The Jam and Joy Division, took longer than anticipated and resulted in a delayed release of the album. But 808 State are not averse to recreating samples or 'counterfeiting' their own when necessary. "We've had to re-create samples a few times," says Graham. "Sometimes you can spend far too much time doing that! There's a sample on Europa that was originally a Motown thing, and you just can't sample Motown at all. So we took the essence of that sample and recreated it in minute detail. It had about eight instruments in it, and took us the whole day to re-do it!" He has come to accept that it's not worth getting upset over prohibited samples. "It's kind of interesting creating your own samples anyway," he says, optimistically. "You see, it's not just to do with how they sound, it's to do with where they've been. So we make something, then record it on to a cassette and re-sample it from that so the quality is reduced. That way you get the right feel to the sound: you don't want gleaming, nice samples, you want a bit of dirt!" The quest for grit extends to the choice of sampler. 808 State have both Akai's S1000 and S1100, but they often go back to the rough sound of the Casio. "The cheesy strings on Lift [from Ex:El are a combination of ARP Quartet and FZ sample," says Graham. "The FZ samples seem to have far more character than the Akai. I'm leaning towards that machine nowadays, because of the lack of quality. It's not awful, it's just a difference in quality which we like. "I've been recording sounds and stuff for years," he continues. "I've got suitcases full of wacky tapes and strange sounds that we're sifting through all the time. The group I used to be in, Biting Tongues, used these tapes for backing before sampling became popular, way back in 1978. So I've always been into using random sounds: I really enjoy that aspect of music. "Of course, we're always looking out for new samples too. Not from obvious places like the TV; I mean, we will use it, but we try not to."  80808080fate Having enough time to do everything they want to do is a problem for the guys in 808 State. "You need to find a balance between your own music and other people's," remarks Graham. But they're still finding time to put out tracks into the clubs under a different name, and there are already tracks recorded for the next album. "We're keen to release some EPs of specific styles; maybe a hard, metal one, and another just of mad, jazzy stuff. "During the Gulf War, we heard that CNN were showing scud attacks on a disco and planes taking off from aircraft carriers while playing In Yer Face and Cubik! So perhaps we should do a concept album for World War Three next..." FM Alive and blipping We interviewed the 808ers between tours: they had just finished two weeks in the UK, supported by a very hyperactive Moby, and were preparing for a 54- date haul around the USA, this time with Meat Beat Manifesto. It's important to the band that they deliver "a top night out", so there's usually a guest DJ to warm the crowd up, plus plenty of lights and visuals. Graham: "An 808 gig is a complete package. You have to get that good vibe going with the crowd." Their studio may be littered with classic analogue kit, but live playing is mainly a digital affair. "It's too dodgy taking out the old synths: things keep going down." says Graham. He and Andy currently hide behind a Roland Jupiter 8, D-50, Juno 106 and JD-800 MIDI'd to an Oberheim Matrix 1000 and Akai S1100. When Darren's not cajoling the crowd and telling them how "absolutely fuckin' marvellous" they are, he drops in samples and plays ambient fills with a collection of records and a couple of Technics SL1200s. He also reinforces the rhythm track with congas, timbale and a Roland Octapad triggering an Alesis SR16 and S1000. That Atari ST at the side of the stage is actually just a decoy: live sequencing is a very rare event. A DAT player provides the usual track backbone instead. "We have used Cubase live, but not on every night of a 54-date tour!" says Graham. "Last time we did a lot of dates, we did get a bit bored with always doing the same thing with DAT, so we took the Atari out and did a few introductory-type things with Cubase and the S1000. "At the moment, a lot of the keyboard tracks are missing on the DAT, so we can make things different every night." In this way, they keep up the enthusiasm for playing live. "You've got to consider yourselves on a big tour," as Graham says. "Live versions of track are always different to the studio versions. Over the years, we've done about eight versions of Pacific, and sometimes I find myself clicking into the wrong one! "One thing we've noticed is that as you go on, your playing gets much, much better. We're going to be shit hot by the time we come back from America!" Using the minimal DAT backing is a compromise; Graham would like to see more flexibility in their live set. "We're planning to get A-DAT for the studio anyway, so we might take that out live," he reveals. "It'd give us the possibility of separating out the basslines and drum tracks, and running a sync track to the other gear. It will give us that manipulation in the mix that gives the music more of an edge." The American tour ends in Hawaii, the US's "808th State" (well, as far as phone dialling codes go anyway).  In yer record collection ...You should make sure you have all these: (Inciden tally, the LP of Gorgeous comes with a free, limited-edition disco 12-inch containing three tracks not included on the CD format.) 808 singles Let Yourself Go/Deepville Creed '88 808 albums: Newbuild Creed '88 ..plus remixes for Jon Hassell (Voice Print)) Wendell Williams (Everybody), Quincy Jones (Back On The Block), Yes (Owner of a Lonely Heart), YMO (Light In The Darkness), Siouxsie and the Banshees (Face to Face from Batman Returns) and Electronic (Disappointed). There was also a mix of David Bowie's Sound and Vision, only available in the US, and a remix of Rolf Harris' Sun Arise: this was never released because it was recorded at a "sensitive time". In other words, Stylophonia by Two Little Boys was released at the same time, and the 808 lads didn't want to look quite as silly as them.  808 Stats So, how did those Mancs make themselves Gorgeous? With the aid of the following: Sexy synthesizers: ARP AXXE Sequencing: Atari 1040FM running Cubase Atari Mega 2 running Cubase ARP Sequencer Other bits and pieces: Alesis Quadraverb And what's on the 808-ers wish list? "A machine that writes lyrics and sings" |

|