| Interview with Graham Massey: 808 State and the Development of Record-making | |

|

Dutch Girl In London 15 December 2015 Link |

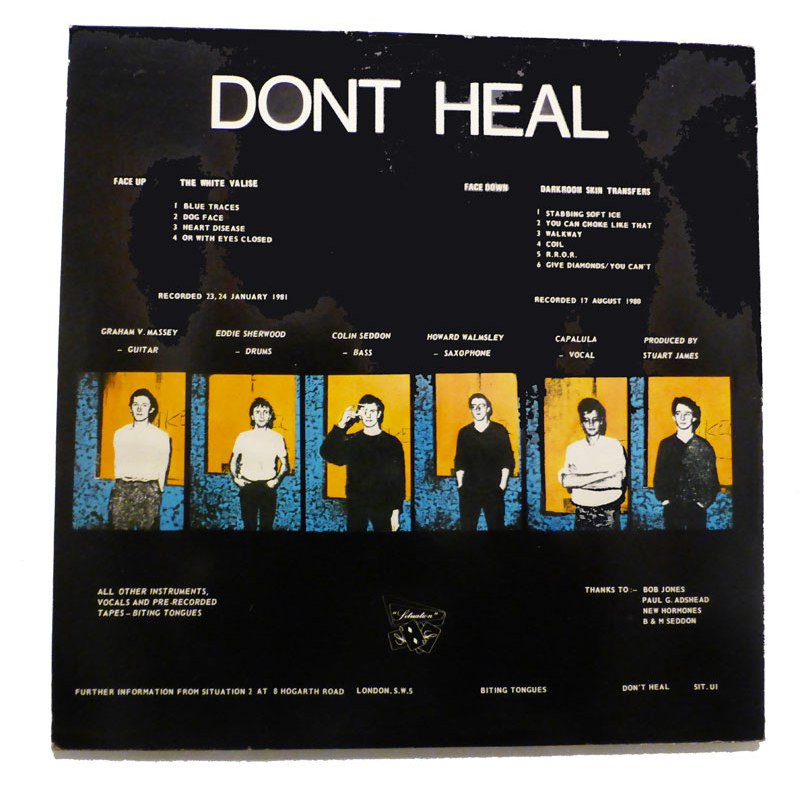

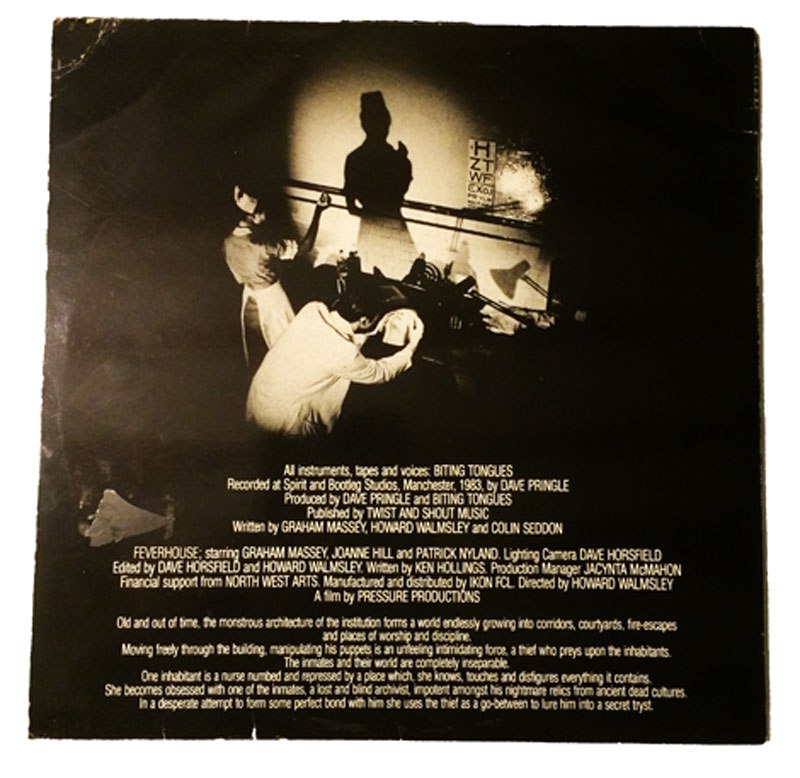

I first saw legendary band 808 State at the London Electronics Arts Festival (LEAF) last March where they played their defining album ‘Ninety’ (1989) in its entirety. Little did I know then that I would be spending a weekend with band member Graham Massey in Sweden that spring for Music Tech Fest. 808 State, who take their name after the Roland TR-808 drum machine, are regarded as pioneers of acid house. They have been touring with ‘Ninety’ for the last year and last June I happened to be in the Netherlands when they played a show at former cigar factory W2 in Den Bosch. Before they were about to play an exciting live show, Graham kindly agreed to do an interview with me.  How do you feel about playing an album that you made so many years ago? Has the process been difficult? Yes, it’s been different from how we would normally do a concert. We tend to build a shape, the peaks, but when we play this album it doesn’t work that way. When we made this album in 1989 we thought very much in terms of albums. Back then you didn’t put your best tunes first, you led into a slow slope that peaked at the end of side A and then you’d start again at side B. So playing the album live in that order feels very unusual, but it’s interesting. We made albums of house music, which was an unusual thing to do as well because that was the era of just 12’’ singles and just music for the dance floor, but I think 808 State was quite unusual in that they still thought in albums. We were brought up on kind of progrock, perhaps not the best way to describe it, but that way of making an album like Pink Floyd would make an album. It would be kind of telling a story, with interludes. It was like a canvas to paint on and you did it in a certain way. There was definitely that kind of thinking in what we were doing. Do you notice a difference in audience reception between when you originally played the album and the audience now? It’s hard for me to judge. I can’t really tell how people receive it. It was different when we did it at that LEAF concert in London as people understood the concept, also because in more recent years people like Kraftwerk have done that format of presenting an album. To be honest, we’ve fought against it for quite a few years. People have been suggesting it for a long time, but it wasn’t till that opportunity at LEAF that we got to play that concert with a really nice PA system and were looked after really well. We trusted the people who ran the festival. And now we’ve done all that work, it seems silly to do it just once.  Do you have any stories about early acid house rave days? In those days music was coming from all over the world. One of the guys in the band had a record store in Manchester. It was a dance music specialist so he’d get music from America, from Belgium, everywhere. The other two guys in the band had a radio show on a local radio station in Manchester so they would play all the import music that was coming into the shop. People recorded it on a cassette. Then we got influenced by all the music that came in and we’d go make records. The whole system was like a loop. At that point we had a few really good clubs in Manchester, so we could make music, take them to these clubs, try them out, see what worked, see what didn’t work, go back, change it. It felt like a laboratory.  Everything in that period was new and fresh and communicating with the world. It wasn’t as colloquial as music was before. When I grew up in Manchester, the Manchester music scene was a very small community of musicians talking amongst themselves and rarely playing outside the city. You were considered lucky if you got a gig in London for instance. In fact, one of the few places where we could get concerts as a Manchester band. I’m talking about the early/mid 80s with a band called Biting Tongues that I was in on Factory Records, was Holland. We used to come to Holland because there were a number of promotors here that were connected to Factory Records. So we would come here and play in Nijmegen. I remember it was a big squat club there. It started off as a big squat and became an established club. And then there was another one in Groningen called Vera, which is still there. Yesterday we played in the Milky Way [Melkweg in Amsterdam] and the dressing rooms were exactly as they were in 1984 or whenever we played there. For me Holland was like an open-minded liberal place that felt very different to play than in England. For instance we could go do radio sessions in Hilversum or they would come out to the Milky Way and recorded there. We couldn’t get that kind of attention in the UK at the time, not easily. So when we came here it was like ‘see, it works!’.   Those Dutch people have good taste!:-) No, it’s just that the Dutch people are kind of open to music. We’d be here and bump into a lot of the interesting American music that we were into of people like James Blood Ulmer and Decoding Society. These were bands in the 80s that were doing very interesting things, they were all like subsidiaries of the jazz musician Ornette Coleman, who just passed away [in June 2015]. We were really influenced by these spin-off bands of Ornette Coleman and we were trying to do something similar in our music. Suddenly we would be on a festival with these guys in Holland. This was the big wide world to us at the time! It was very exciting as a young 20-year old musician to be somewhere where people could meet. The world has changed a lot. It felt so much smaller back then. Not because we were young, the networks were just different. The internet didn’t exist so everything became ‘blowing up’; you know when you heard about a record and your imagination connected to it and blew it up to wherever it was in your imagination. But now there is so much information. The facts are somewhere so you don’t really use your imagination in a way. You just look it up, but back in that time you would make it up in your imagination. About Ornette Coleman, you have any memories or anecdotes? Sounds like it [the 1980s] was a very exciting time. Yeah it really was because there were lots of things happening with technology in the 80s. People getting hold of new technology, going off and see what they could do with it. For instance, some of the most interesting electronic music to me wasn’t to do with pop music, it was to do with jazz music a lot. The American band Weather Report were quite experimental, but they were a band that developed. Every album they did was different. They were excellent musicians who were willing to experiment and go into a different direction. They were very aware of texture and colour in music. Their keyboardist, Joe Zawinul, played with Miles Davis. He was a jazz guy who took to synthesizers very early on. He was kind of like Herbie Hancock, but had come from jazz. But he was very different from Herbie Hancock in that as a synthesizer player he explored colour and texture much more than someone who just messes around with the synthesizer and gets the first thing that comes out of the synthesizers. He was one of my favourite musicians and he was doing interesting things with Midi technology, which is when you join keyboards together and they all talk to each other, and drum machines. So in the mid-80s this kind of technology was happening and you could start a one-man band with that, have drums and keyboards. He did a very interesting record called Dialects that I absolutely loved in the 80s and I think that was a big influence on how I was thinking with synthesizers in the mid till late 80s. So when it came towards making house music, half of my head was going that way. I liked the colour of his records and the landscapes. Then you also had a lot of pop music in the 80s that used synthesizers. There were these electronic bands around, using the technology and inventing the language. Kraftwerk being the first one, then New Order coming after that. There was this language of electronics around, but there were also these other guys doing some interesting stuff that was part of the language that we took up. Relating to technology, what do you think of the resurgence of synths, of the Eurorack modular gear and all the new Roland stuff that’s out now? I think it’s really good people are wanting different things from synthesizers. That whole world has opened up recently, in particular with the Euroracks as you say. And even a company like Roland now have brought out a modular system that interfaces with Eurorack equipment, so they’re joining the conversation. Plus all the younger people who have started working for these companies are getting in it now as well. So that whole world has changed. Although there are a lot of people working with modular synthesizers, that doesn’t necessarily result into interesting music. I look at a lot of synthesizer sites because I’m interested in that area, but notice so little music comes out from there that is emotionally engaging for me. I see them as tools, but ultimately you have to think ‘music’ and not just ‘synthesizers’ because that’s just like guitarists noodling to me. It becomes an unbalanced thing, because after all they are tools to add to a bigger music to me. Probably the impact of all this technology will result in more collaborative setups with synthesizers. We got involved in making this 808 movie documentary recently and it’s a film about the 808 drum machine. One big revelation in that film to me was that they used faulty transistors in the production because they were cheap. For every transistor that was made back then, 3 out of 10 were defective, but actually the hi-hat sounds and certain sounds in the 808 needed these defective transistors. That’s why they never made them again, because they ran out of the faulty transistors. It would make perfect sense to manufacture them again because they’re selling for £3000 second-hand. For years and years we had been asking that question. Now it’s finally answered in this film. You worked on a film score some years ago. Are you interested in writing for film again? I’ve done a number of films for my sister-in-law Lucy Beech. And there’s another artist called Chris Paul Daniels from Manchester who works in a similar area and I’ve been working with him on a couple of projects. It’s very collaborative in that I’m throwing stuff at him and he’s coming back with other ideas. It’s really easy to Ping-Pong ideas around right now. Some of the filmmakers got the same language as the musicians now and can come back with ideas. I’m really enjoying that at the moment. I always thought that doing film music would be a form of artistic expression where you could be indulgent. It’s absolute the opposite in a way in that you are serving something else so you have to take it really back, minimally, and it’s amazing how little you can get away with. It’s about total minimalism a lot of the time. It’s very good discipline for me because I’m much more likely to be very layered and very complicated. It’s the complete opposite of what I would normally do, so it’s good exercise. Final question. You must’ve heard it many times already so I hope you don’t mind me asking. You co-wrote and co-produced a couple of tracks with Björk. How did that come about? Well she got in touch with us. She’d heard some of our earlier records and wanted somebody to work with primarily for beats and she thought we did interesting beats. She played on two tracks on our album XL before Debut. She wasn’t that phenomenon that she is now, at that point yet. The stuff that I worked on was originally for Debut, but ended up on Post. It ended up on Wikipedia somewhere that I produced some of the stuff on Debut and it was just some Wikipedia mistake that will just follow you around all the time. It must really irritate her completely! We had a lot in common because she’s come through the punk thing, she’s born with that anarchy, very anti establishment thing. She was in this band Kukl and they used to play with bands like Crass, the proper anarchy anti-establishment noise bands. She’s come from a real extreme end in music and I also have experience of doing that kind of anarchic noise punk thing. We had a band called Danny and the Dressmakers, that was just noise, stupid nonsense. Then we got into something more experimental in the 80s, this kind of post-punk thing where all these different ideas were played out, but in a much more kind of pop way, more organised kind of way, more of a production way. People were experimenting in production a lot more at the time, which then led towards electronic music. So, in a similar way we followed similar paths and we had a lot in common and felt very comfortable in the references as we both liked a lot of jazz. When I say that, you know jazz is such a big area, but I mean some of the more interesting stuff in jazz. We liked very similar artists, people like Rahsaan Roland Kirk. That’s the kind of music that we played a lot. It felt very empathic, is the word. [Words: Dutch Girl In London, Photos: Dutch Girl In London / Sandra Leijtens Photography] |

|